The Urban Policy Lab’s “Dispatches from Abroad” blog series provides an opportunity for students at the Munk School of Global Affairs and Public Policy to share their experiences working or studying in cities outside Toronto, whether during their internships, while on exchange, or via extracurricular activities. In this dispatch, Katerina Stamadianos, a second-year Master of Public Policy student, reflects on her academic exchange at the Hertie School of Governance, in Berlin, and what the experience taught her about parks policy and public space.

You know the drill. Young twenty-something girl goes on exchange to Berlin and is here to tell you about how much better things are in Europe. Swears she has found herself and will never be the same – ad infinitum.

I’ll spare you from the exchange student trope – all to say, this blog post is about a park not because I’ve got the girl-abroad glasses on. This blog post is about a park because my flat in Berlin is situated next to a really, really great park – Park am Gleisdreieck. Living next to am Gleisdreieck has gotten me thinking about why going to the park seems to be a more popular activity in Berlin than Toronto, and what Toronto may be able to do to get more people into public spaces.

Park am Gleisdreieck

Park am Gleisdreieck started out as every great urban project does: with the intention to be built into an intra-city motorway. Sized at about 3.15km2, Park am Gleisdreieck was once an old rail line that had come to house its own biotope due to inactivity during the time of a divided Berlin. Plans to install a motorway were opposed early in the planning process, with citizens groups fighting the proposal dating back to the days of West Germany. By 2006, citizens groups had established their interest in shaping the proposed parkland, and several levels of consultations with the public had created a bank of citizens concepts for how the space should evolve.

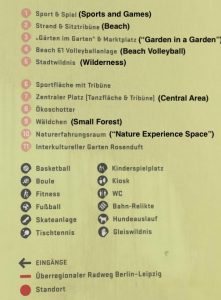

This intensive community consultation process led to two contradictory conceptualizations for the park: one side wanted to retain the park’s calm and natural characteristics, while the other wanted the park that offered a significant amount of programming and areas for sports and activities. Harmonizing these two concepts, the planners proposed the “park of two speeds”, which would incorporate elements of both conceptualizations. Today, am Gleisdreieck is a celebrated public space that is split into the ‘Ostpark’ and the ‘Westpark’, the former focused on the space’s unique environment and the latter offering several sports/activity areas, including trampolines (a personal favourite), a beach volleyball court with its own beach bar, and more. The park also integrates the neighbouring technology museum, holds several small stalls for snacks and drinks, and even boasts a brewery. Note, also, that the future of am Gleisdreieck is still being shaped, as several developments have been proposed around the park.

Seating incorporated into an old industrial area in the park.

The Popularity of Parks in Berlin

From my own observation, Park am Gleisdreieck is widely popular and brings in impressive numbers of visitors. But beyond am Gleisdreieck, parks in Berlin take in large numbers of locals simply looking to relax, socialize, or be active. While it would be an understatement to say that this practice isn’t visible in Toronto, it would seem, from my experience, that the use of public parks is higher in Berlin than in Ontario’s capital. Any Torontonian knows how busy Trinity-Bellwoods can get on a warm weekend, but this seems to be one of the only examples of the city approximating European park culture. What is it that brings people to the park in Berlin?

If Park am Gleisdreieck is any indication, the successful translation of citizen interests into the features of the Ostpark and Westpark may have a large role to play in the park’s popularity. The planning process for the park has been lauded largely as a success, which can also be seen in the use of its various amenities by people young and old. The park simply has a lot to offer, as opposed to the rather standard tennis-court-and-children’s-playground combo seen around downtown Toronto.

A partially translated legend of Gleisdreieck’s offerings.

Another answer, at least partially, may be in the city’s public drinking laws. If you go to any park in Berlin, the odds are high that you’ll see a large number of patrons nursing a beer as the sun sets. These park-goers are not being rowdy or disruptive, but are instead enjoying some quiet time with friends – one of the primary goals of the modern park. When the weather is inviting, people are incentivized to leave the house to grab a drink with friends without having to be confined to an indoor area or patio. This, in some ways, opens the park up even more to the feeling of being a space for citizens and for socializing. Perhaps something is to be said for city’s approach to public drinking in contributing to a lively park culture in Berlin.

There is also the idea that European cultures may be more amenable to utilizing parks than the dominant culture within Toronto. The clearest manifestation of this is in the work-life balance of either city. All stores and businesses in Berlin (apart from restaurants) are closed on Sundays, which has redefined the day as a time for family, friends, and leisure – which, in many cases, drives people to the park. There also seems to be an inclination on the part of North Americans to prefer outdoor time in their backyards in lieu of the park. Europeans, and Berliners in particular, mostly live in apartment complexes, which means that public spaces are the primary outdoor spaces. These are just two examples of cultural differences that could plausibly influence the difference in park use in either city. These cultural differences are likely the hardest to rectify, given their deep root in the identity of either city. People often attribute Berlin’s idiosyncrasies and quirks to the city’s unique history. Communism, the fall of the Berlin Wall, and the subsequent lawlessness of the city are spun into explanations for everything from living patterns to street food.

There doesn’t seem to be a clear, measurable answer to the question of whether getting more people to the park in Toronto is achievable through policy alone. What is clear, however, is that public spaces can be best defined by the citizens that use them. Park am Gleisdreieck is a great example of citizen engagement in the creation of a public space, and one that can be used to motivate citizen design in Toronto. Who knew a park could get me thinking this much?

Katerina Stamadianos is a Master of Public Policy student currently studying at the Hertie School of Governance in Berlin. She is passionate about urban issues, and is especially interested in how to best preserve and support a vibrant arts and culture scene within cities.